The Backstory: The Eye

This 1928 hurricane was one of the deadliest

It’s September, and while that means back to school and readying for fall in other parts of the world, here it means the bowels of hurricane season.

This month, instead of sending out a short story and then a backstory companion piece, I’m switching it up. So here is the history and context for the story first. It’s fascinating in the dark way only natural disasters can be.

Now, back to storms. They are featured a lot in my writing. In South Florida they can be sudden and fierce and then vanish as if they never were. The frequency is such that you can almost forgive people for not taking storm warnings seriously—almost. At least today we have the benefit of having a better idea of what’s coming and evacuation plans in place. Now go back to a time when people didn’t have the benefit of a few days head start on a potential hurricane or the added accuracy of where it was going to make landfall, and you have a recipe for true disaster.

One of the deadliest examples was the Okeechobee hurricane in September of 1928. The damage it inflicted on the coast was terrible, but the havoc it wreaked on the communities surrounding Lake Okeechobee was apocalyptic. The official death toll from the storm was initially a little over 1,800 (the National Hurricane Center later changed the estimate to 2,500), but the true number may never be known since so many bodies were lost to the Everglades and never found. Many that were found ended up in mass graves.

The storm’s ruthlessness and devastation, in particular to the African American and Bahamian farmers of the area, inspired a part of Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God.

“It woke up old Okechobee and the monster began to roll in his bed. Began to roll and complain like a peevish world on a grumble. The folks in the quarters and the people in the big houses further around the shore heard the big lake and wondered. The people felt uncomfortable but safe because there were the seawalls to chain the senseless monster in his bed. The folks let the people do the thinking. If the castles thought themselves secure, the cabins needn’t worry. Their decision was already made as always. Chink up your cracks, shiver in your wet beds and wait on the mercy of the Lord. The bossman might have the thing stopped before morning anyway. It is so easy to be hopeful in the day time when you can see the things you wish on. But it was night, it stayed night. Night was striding across nothingness with the whole round world in his hands.”

--Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God

There were smaller levees in place to keep the water in the lake, but it was no match for a storm so strong. To understand how the storm could end the lives of so many, so far inland, you first need to comprehend the size of Lake Okeechobee.

The largest lake in the Southeastern U.S., Okeechobee covers 730 square miles. If you look at a map of Florida it’s the big dot, like an eyeball on the snake head that is South Florida. The lake is also pretty shallow for a lake of its size, which is bad when a storm comes. A category 5 storm like the one in 1928 easily churned up the water from the lake and sent it flooding into the low-lying areas around it. The waters reached as high as 11 feet in some places. With nowhere to go, thousands drowned.

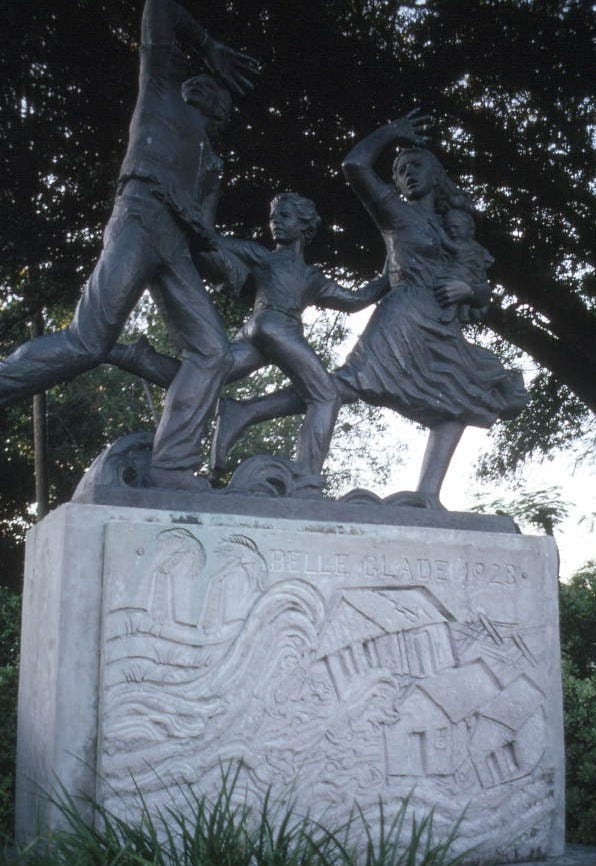

Sadly, this unprecedented loss of life in this rural area resulted in many of the victims of the storm being burned and buried in mass graves. A disproportionate number of them were the African American and Bahamian farmers who worked the land. Years later a small memorial was erected to acknowledge and honor those victims.

Today if you drive by Lake Okeechobee, you won’t see the water from the road. You’ll see the Hoover Dike with an elevation of 30 feet that’s designed to keep anything like the aftermath of the 1928 hurricane from happening again. It’s a pretty reassuring sight.

If you haven’t already, don’t forget to check out our latest giveaway. Florida fiction must reads can be yours! Giveaway ends 9/13/24.